From Karl May to Heinz Erhardt: The German-Macedonian Relationship in the Long 20th Century and the Painful Transformations of European Order

Stefan Troebst (SFB 1199, GWZO & Leipzig U)

Publication Date

September 2018

Type

Media

In the “long” 20th century, Germany and Macedonia are connected by a special relationship, in particular in the German perception of Macedonia. But why was that so? Why should this small part of the central Balkans be of any importance to a great power like the German Empire, the Weimar Republic, and Nazi Germany, later to a divided Germany and ultimately a reunited Germany?

The period of the most intense German interest in Macedonia were, for certain, the years of the Weimar Republic, that is from 1919 to 1933. At that time, German public dicourse in newspapers and other periodicals abounded with information on Macedonia and the Macedonian Question. How is that to be explained? Because large segments of German society – feeling defeated in World War I and humilated by the Treaty of Versailles of 1919 as well as desperately seeking this treaty’s revision – looked for positive role models in its urge to topple the detested “Versailles System” imposed by the victorious Entente powers. And this role model was found in the Balkans: in the form of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization abbreviated IMRO. Operating with Italian support against the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (from 1929 on: Kingdom of Yugoslavia), first by guerilla tactics from Bulgarian and Albanian territory and then by terrorist means, the IMRO violently challenged the post-war order installed at the Paris Peace Conference. Accordingly, IMRO fighters and assassins, some of them women, became celebrated heroes for many Germans. The German press of all political colours, from the extreme right to the communist left, praised the example of the Macedonians who were willing to sacrifice their lives for their national idea of a unification of all three parts of historical Macedonia, be it as an autonomous part of Bulgaria, be it as a “second Bulgarian state”. “These men know how to treat Europe the right way”, wrote the daily Rheinisch-Westfälische Zeitung of Essen on 21 March 1930 – obviously in contrast to German “Paneuropeans and pacifists”, who in this perception cowardly accepted the dictate of the victors at Versailles.

While the admiration for the IMRO’s struggle against the post-war settlement was widespread in Weimar Germany, journalists and scholars fiercely debated the ethnic outlook of the population of (Yugoslav) Vardar Macedonia. The majority shared the view that the Slavic-speaking Orthodox Christians there were Bulgarians, while the contemporary doctrine of Belgrade was rejected. Only the prominent social democrat Hermann Wendel supported the offical Yugoslav view that they were Serbs. The modern interpretation that next to Bulgarians and Serbs a separate Macedonian nation existed was propagated only by mavericks in politics and media, like the conservative journalist Max David Fischer, the editor of Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, or the political chameleon Bodo Uhse, in the late 1920s a member of Hitler’s Nazi Party who later turned communist and after the war became an official in the German Democratic Republic. In an article in the journal Nationalsozialistische Briefe from 1 September 1930, he called for German political support of “the unrelenting fighters for the liberation of Macedonia” and ended with the slogan: “Macedonia to the Macedonians and Germany to the Germans.”

“Karl May. Der Schut“ © By Verlag Friedrich Ernst Fehsenfeld (Karl-May-Wiki) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons, Link

But also when we look at Weimar Germany’s book market we find a large number of publications on various subjects dealing with Macedonia – predominantly on biology, zoology, hydrology, social anthropology, linguistics, geography, geology, and so on. But how come? For two interconnected reasons: First, from 1916 to 1918, some 30,000 German troops from the army’s battlegroups “Below” and “Scholtz” fought against the forces of the Entente on the almost 500-kilometer long Saloniki front cutting across Bulgarian-occupied Vardar Macedonia. Not only Prilep, where the German headquarters were located, and – temporarily – Bitola but also Veles and Skopje were full of German soldiers. This resulted in the publication of not only memoirs but also of kitschy novels. And second, with consent of the Bulgarian occupation authorities, the German emperor Wilhelm II and the Ministry of Culture of Prussia co-financed a large field expedition of German academics to Vardar Macedonia, the Mazedonische Landeskommission (abbreviated Malako). Some 100 scientists of all fields of the humanities and natural sciences sprawled over all of Vardar Macedonia north of the front line and conducted fieldwork. The larger part of the results of their research, mostly books, was published during the 1920s like, for instance, the authoritative monograph Ethnographie von Makedonien (The Ethnography of Macedonia) by Gustav Weigand of Leipzig University, a linguist and staunch German supporter of the IMRO.

“Gustav Weigand. Ethnographie von Makedonien” © Gustav Weigand [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons, Link

Yet, the German interest in Macedonia, based first of all on economic and military considerations, had its roots even in earlier decades. German industrialists, merchants, engineers, missionaries, and others discovered the late Ottoman Empire as a promising field of action and of business opportunities. In his fabulous book Der Traum vom deutschen Orient (The Dream of a German Orient) from 2006, Malte Fuhrmann describes Ottoman Macedonia as a “German colony in the Ottoman Empire”.

The German presence in the Vardar Valley was astonishing since up until the end of the 19th century the Balkans in general and Ottoman Macedonia in particular were perceived in the best case as terra incognita. More often, however, it was considered a hostile environment, characterized by banditry, blood revenge, malaria, and endemic corruption – at that time the Ottoman terms başı bozuk, yatağan,and bakşiş became part of the vocabulary of the German language. An impressive proof of this negative image is a series of adventure novels by the most popular German writer of the time, Karl May, published in the 1880s: In den Schluchten des Balkans (In the Gorges of the Balkans), Durch das Land der Skipetaren (Through the Land of the Albanians), and Der Schut (meaning “The Yellow One”, from Serbian žut). Without ever using the regional term “Macedonia”, May located these novels in the Vardar part of Macedonia – between what he called, according to Ottoman administrative nomenclature, “Ostromdscha” (Ustrumca), today’s Strumica, and “Kalkandelen”, today’s Tetovo in the Republic of Macedonia The picture painted by May of the region and its inhabitants resembles more a collection of prejudices than first-hand experiences. And indeed May never set foot on Balkan soil but relied exclusively on entries in contemporary German encyclopedias and on travelogues.

Going back to World War I, namely to the remnants of the German presence on the Saloniki front, the most visible one is the monumental Totenburg (literally, Castle of the Dead) on a hilltop in the Western outskirts of Bitola. Constructed in the mid-1930s, it houses the remains of some 3,000 German soldiers. Furthermore, in downtown Prilep a war cemetary for German as well as Austro-Hungarian, Bulgarian, and other soldiers was built. It contains a separate grave for the son of Weimar Germany’s first president of state, Friedrich Ebert, Private Heinrich Ebert, who in 1916 was wounded in the battle of Mt. Kaymakchalan and died in early 1917 in the German military hospital of Prilep. Finally, near Gradsko in the Vardar Valley, there is a now defunct narrow-gauge railroad tunnel – built, as a memorial plate says, on the order of Emperor Wilhelm II by Field Marshall August von Mackensen in 1916. Today the tunnel is used for the production of mushrooms – a rather successfull conversion of a military installation into an economic and thus a useful one.

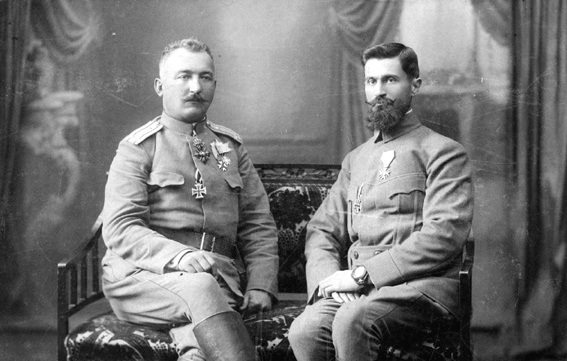

“Bitola Macedonia“ © Macedonie Travel Guide, Link

What during World War I was called the German-Bulgarian brotherhood in arms was in fact a German-Bulgarian-Macedonian brotherhood in arms since many leaders and the rank and file of the mentioned IMRO served in the Bulgarian army, the ally of the Imperial German Army. Two of the top IMRO officials and at that time Bulgarian army officers, Captain Todor Aleksandrov and Lieutenant-General Aleksandăr Protogerov, were awarded the German military order of the Iron Cross by Emperor Wilhelm II personally in Nish in January 1916. A later result of this close German-Macedonian military and also political cooperation were Protogerov’s attempts in the early 1920s to talk various governments of the Weimar Republic into a joint German-Macedonian anti-Versailles action, for example in the form of parallel terrorist attacks in Polish Upper Silesia and in Yugoslav South Serbia, that is to say Vardar Macedonia. Since the leaders of the Weimar Republic in Berlin were desparately grappling with a large number of more pressing problems – loss of territory and colonies, reparations, French occupation of the industrial Ruhr district, demilitarization, uprisings by communist and right-wing paramilitaries, strikes, inflation, and so on – the IMRO’s proposals were taken into consideration, but ultimately declined.

“Alexander Protogerov and Todor Alexandrov” © Unknown author, via Wikimedia Commons, Link

Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 had no immediate impact on how Germans perceived what was going on in the Balkans. Yet Macedonia was still on the mind of German readers. In 1938, Hans Ehrke published a large number of copies of a soldier’s novel entitled Makedonka. Ein Buch der Balkanfront (The Macedonian Tune: A Book on the Saloniki Front), and third-class writers like Heinz Rettenbach and Robert Felix (aka Felix Solterer) became popular through adventure novels and detective stories with Macedonian settings. However, when, on 27 August 1939 – three days after the signing of the pact with Stalin and four days before the German attack on Poland – Hitler received the British ambassador Nevile Henderson, the Führer made a cryptic remark: “I can no longer tolerate Macedonian conditions [mazedonische Zustände] at my border [to Poland].” The barely hidden message was that Germany would soon start a military operation against its Eastern neighbour – which it did. In 1987 the Macedonian playwriter and poet Jordan Plevneš published a play using this quotation by Hitler as a title, and that in German: Macedoniše cuštende. JU-antiteza (Macedonian conditions. YU-Antithesis).

“Hans Ehrke. Makedonka” © Makedonets, Link

Similarly, like World War I, also World War II brought Macedonia into the focus of German military expansionism. Next to Bulgarian occupation forces, also units of the Wehrmacht were stationed in Vardar Macedonia, both taking active part in the deportation of some 7,000 Jews of Vardar Macedonia and Southern Serbia to the death camps at Treblinka in the spring of 1943. While the Skopje historian Aleksandar Matkovski already in the late 1950s undertook meticulous research on the Holocaust in Bulgarian-occupied Vardar Macedonia, it took his colleagues in Sofia another half a century to come up with first scholarly publications on this tragic topic and to confront their own public with it.

Also in 1943, due to the Italian retreat from the Balkans, the Wehrmacht and SS sought the cooperation of IMRO’s leader Ivan Mihailov, then in exile in Zagreb, at that time capital of the Croatian Ustaša state. The aim was to set up an auxiliary occupation force of up to 12,000 Macedonian volunteers in German-occupied northwestern Greece. However, in reality the strength of this Okhrana (as this unit was called) never exeeded 500 men. Finally, during the hectic retreat of German troops from Greece and the Balkans in 1944, Hitler offered to nominate Mihailov as head of a Macedonian state under the aegis of the Third Reich. After a two-day visit to Skopje in early September 1944, Mihailov declined the offer due to the swiftly approaching Red Army from the east and the activities of the various Macedonian partisan groups in the region. In October, the Wehrmacht staged a massacre in the village of Radolišta/Ladorishte near Lake Ohrid, cruelly killing 80 inhabitants, and in November the last German army units blew up the Vardar bridges of Skopje – only the Ottoman Stone Bridge was spared.

The German defeat in World War II, the rise of communism in the Balkans, and the division of Germany into four zones of occupation as well as the Tito-Stalin split interrupted the German-Macedonian communication lines from previous times. One of the few exceptions was the support by the German Communist Party in the Soviet Zone of Occupation of Germany for the Greek Communist Party and its Democratic Army of Greece, with its strong Macedonian components. The Aegean Macedonian Andon Sikavica was one of the liaison officers between the East German communists and the partisans during the Greek Civil War – before in 1950 he was expelled from the Greek Communist Party as a “Tito fascist agent” and exiled to a village in Romania.

Yet a decade after the founding of the German Democratic Republic and the Federal Republic of Germany in 1949, more sustainable contacts between the two Germanies and now Yugoslav Macedonia were renewed. Leipzig University, then named after Karl Marx (not Karl May!), established an academic cooperation with the Institute of National History in Skopje, and at the neighbouring University of Halle a lecturership for the Macedonian language was created. On the other side of the German-German border, among the many Gastarbeiter from Tito’s Yugoslavia, also a relatively small number of Macedonians arrived, particularly to Bavaria, Baden-Württemberg, and West Berlin. The western half of this divided city came to play an important role for today’s Macedonia, and that for two reasons: First, it became a stronghold of Dragan Bogdanovski’s Movement for the Liberation and Unification of Macedonia (DOOM), and second, the Jakovleski brothers from the village of Zubovce, Gojko and Mane, both close to Bogdanovski, opened on the central Kurfürstendamm Boulevard their restaurant Novo Skopje. It soon became a favorite meeting place not only of Macedonians and Germans, but also of several dozens of other nations – and with its open-fire charcoal grill functioned up to its closing in 2003 as an “ambassador” of Macedonian cuisine.

“Novo Skopje”

After Macedonia had been carefully steered through the post-Yugoslav imbroglio into a still shaky independence by its first president Kiro Gligorov in 1991 and recognized by reunited Germany in 1993, bilateral relations considerably intensified. This was not the least the merit of the first German diplomatic representative to Skopje, Hans-Lothar Steppan, who arrived as consul general in 1992 and retired in 1996 as ambassador, succeeded by Klaus Schrameyer. In 2004, Steppan published a voluminous book on imperial Germany’s policy toward the Macedonian Question in the 19th century entitled The Macedonian Knot. And he was an ardent collector and promotor of modern Macedonian art.

The other German who became popular, even famous in now independent Macedonia, was the social democratic politician Walter Kolbow whose Büro Kolbow (Kolbow Office) in 1999 coordinated German aid during the arrival of the refugee waves from Kosovo. And finally, in order to stop armed conflict between Albanian insurgents and the Macedonian security foreces, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) Operation Amber Fox was set up in 2001 in western Macedonia under German command led by Brigadier General Heinz-Georg Keerl.

So to sum up: During most periods of the “long” 20th century, a vivid, if not always clear, perception of Macedonia prevailed in Germany – of course, with ups and down. Currently, we witness an up: For instance, Macedonian literature is popular in Germany, as the sales figures of translations of Vlada Urošević’s Mojata rodnina Emilija (My Cousin Emilia), Luan Starova’s Vremeto na kozite (Time of the Goats), or Petre Andreevski’s Pirej (Witchgrass) demonstrate. In football, fans of Vardar Skopje and of Schalke 04 celebrate their friendship occasionally even in Greek stadiums. In the political realm, federal chancellor Angela Merkel for now thirteen years has been a champion for Macedonia’s accession to NATO and the European Union. And in April 2018, even the case of the German citizen Khaled Al-Masri, detained by Macedonian security forces in 2003 under the suspicion of being a member of al Qaeda and later handed over to the US Central Intelligence Agency for internment in Guantanamo, was settled by an indemnity paid to him by the Macedonian government. Today, an estimated number of 70,000 Macedonian citizens live in Germany – the number of Germans in Macedonia is, of course, much smaller.

At the end, an hommage to the still famous German actor and slapstick comedian Heinz Erhardt, a native of Riga (then tsarist Russia, today Latvia), in his West German movie Unser Willi ist der beste (Our Willi is the Best) from 1971. In this movie he takes on the role of a television cook that creates in front of the camera a new dish called “Macedonian rabbit in Albanian pepper sauce”. Although most moviegoers in Hamburg, Cologne, and Munich at the time hardly deciphered this innuendo to interethnic relations in the then Socialist Republic of Macedonia (within the then Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia), Heinz Erhardt definitely did. After he had put all ingredients of his hot and spicy dish into an electric mixer, he pushed the button – and the whole thing exploded. That was then, in the 1970s, of course, an overly pessimistic message, yet, as we today know, not a completely unrealistic German vision of Macedonia.

Biographical Note

Stefan Troebst studied history and Slavic studies from 1975 on in Tübingen (then West Germany) and at the Free University of (then West) Berlin, Sofia (Bulgaria), Leningrad (today St. Petersburg, then Soviet Union, today Russian Federation), Skopje (then Yugoslavia, today Macedonia), Bloomington, Indiana (USA). In 1984, he obtained a PhD degree in Russian and East European history and Slavic studies at the Free University of Berlin where he also completed his habilitation in 1995. After terms as assistant and associate professor at the Free University of Berlin, in 1992 he left academia and became a German member in the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE) missions of long duration to former Yugoslavia and the former Soviet Union. In 1996, he was nominated founding director of the Danish-German European Centre for Minority Issues, and in 1999 a full professor at Leipzig University. His research focuses on the history of the subregions of Europe’s eastern half (Southeastern Europe, East-Central Europe, Northeastern Europe and Muscovy/Russia/Soviet Union), on the modern history of Europe, on the history of international relations and international public law, as well as on politics of history and cultures of remembrance in contemporary Europe.